What a joy it was to find Claude Hayward alive and well and ready to reminisce and think about the San Francisco Diggers back in 2011.

Claude was a shadowy figure in the Diggers — mentioned here and there by name in various accounts and memoirs, famously rendered as mysterious and evasive by Joan Didion (!), the one living guy who could talk in depth about the late Chester Anderson, his partner in printing over 600 broadsides (many of them Diggers-penned) as the Communication Company. Amongst Diggers and children of Diggers, wild stories abounded about Claude’s life before, during and since the Haight. I thought he might be hard to find. But he was right there all along, online, active on Daily Kos and easily reached by email.

I interviewed Claude in a San Francisco backyard on October 2, 2011. We were both in town for the public memorial to the recently departed Peter Berg. I think we were eating apples and drinking coffee. We got a lot of talking done; what follows is pretty much how the conversation went, with some edits for clarity, and some later additions and deletions from Claude.

In 2021, the Diggers are little-known. But in 1966-8, such was the Diggers’ presence and notoriety that seemingly every reporter filing a story on the Haight included the Diggers in their account. “A band of hippie do-gooders,” said Time magazine. “A true peace corps,” wrote local daily newspaper columnist (and future Rolling Stone editor) Ralph J. Gleason. The Beatles’ press officer Derek Taylor would write, “[The Diggers] were in my opinion the core of the whole underground counterculture because they were our conscience.”

This is the eighth interview in my series of Diggers’ oral histories; the others are accessible here. For more information on the Diggers, consult Eric Noble’s vast archive at diggers.org

I have incurred not insignificant expenses in my Diggers research through the years. If you would like to support my work, please donate via PayPal. All donations, regardless of size, are greatly appreciated. Thank you!

— Jay Babcock (babcock.jay@gmail.com), October 2, 2021

Jay Babcock: What’s your background? Where did you grow up?

Claude Hayward: My mom’s dad had come over from Germany in 1930; he apparently got a job and made enough money in New York City to bring his family over five years later. Whether he was overtly political or he was just not going to tolerate this crap in Germany and managed to get himself out, I don’t know. He was working class, made stuff with his hands. My mother was born in Germany. She was 9 years old when she got here in 1935. She grew up on Long Island, met my dad at the Grumman Aircraft plant where she and her dad and my dad were all at work building airplanes just before the end of the war. I was born in Brooklyn in 1945.

I lived in Brooklyn in a couple places, then my mother re-married when I was 6 and we lived for part of a year in Greenwich Village, where my stepdad had an apartment. And then we moved out to New Jersey in 1952, some funky place in what’s now called Piscataway, outside of New Brunswick, and I grew up there, that was my boyhood. More country than not—pretty much free to run around, the woods, there were animals to be seen, there was a dairy farmer over the hill and all that. All kinds of Revolutionary War and pre-Revolutionary War ruins and stuff. Apparently Washington camped the Army right there. It was right across the street from Camp Kilmer.

What was your mother doing?

She was being a housewife. I have two half-brothers and a half-sister. They’re younger than I am. My mom took college classes as she could all through her family raising years, and eventually got a degree in English and a teaching credential in German, her native tongue. She was a mighty sharp cookie who somehow managed to impart some lasting values to me.

And your stepfather?

He was a broadcast studio engineer for WABD-TV Television in New York, which was actually the first commercial television station, created by Allen B. Dumont, the engineer who invented the method of mass-producing TV (cathode-ray) tubes that made the explosion of TV into American culture in the early ’50s possible. They were really pioneering stuff. They did Captain Video and Video Rangers live in the studio, 5 o’clock every afternoon. They did other stuff, just taking the camera out into the streets. Nobody had done that. They didn’t know what the fuck they were doing. They were trying to learn how to use this new medium.

So I was six years old and in a fifth-floor walk-up apartment with a shared toilet in the hall. And I had my own television set! With tubes and a screen about that big. My stepdad was the kind of guy that could monkey around and fix it, he had boxes of tubes and resistors and capacitors and all that.

TV was the beginning of the great homogenization of American culture. That’s all you talked about in school: “Did you see Disneyland last night?” Which meant, did you have a television set? These were black-and-white TVs; color hadn’t gotten there for another couple of years. I remember hearing schoolmates talking like what they had heard on TV the night before, imitating the mannerisms and idioms of speech.

We got out of there in ’59. My stepdad got a job to build the educational television station at Michigan State. I was there when they did the first live broadcast of a basketball game. Two semi trucks, with gigantic cables going out across the parking lot, the very first video tape recorders. Big Ampeg machines with two-inch tape. He was in at the beginning of all that. And he went on from there. He built the education television station for Santa Monica City College — KCRW — and he also worked in Las Vegas, put together the educational television station there at UNLV. He moved around and managed to get sideways with everybody and had to go find another job. I think the last job he was doing was working out at the Northridge campus in television, teaching people how to do the knobs and stuff.

He ran the radios for a group of tanks crossing France to liberate Europe and God knows what he saw. He never spoke of it. Came out of it bent, but managed to hold it all together long enough for his family to disintegrate around him as the ’60s crashed through. I, of course, had gotten away from that as soon as I could, by mid-’64.

All my family are builders. We learned that you could just do it. My stepdad got a Sears-Roebuck catalog and converted the coal furnace in the basement of the house to an oil-burning furnace by himself, soldering copper parts with a gasoline blowtorch. And what I learned from that was, Well yeah you just do it! There’s no sense of, I can’t do that, or, I’m not qualified. I think that’s got to be the most valuable lesson I ever had.

So you went to high school in…?

I went to high school in East Lansing, Michigan, which is the company town of Michigan State. As you can well imagine it had an ace high school. It was the school to beat in Michigan, academically. So, I got a really good public school education. I look back now and I realize just how good that was. I was a National Merit runner-up. I shoulda gone down that academic trail, in terms of the direction I was pointed in. Would have been an Eagle Scout, if I had gotten around to submitting the paperwork, but by then I was already wandering off the reservation.

We get to California in ’63 after I graduate, we’re in San Diego when Kennedy gets killed, and then we’re up in L.A. a few months later. And I started hanging out. The January 1, 1964 Los Angeles Times had a Sunday supplement spread on the “vanished Beat scene” down in Venice. By then they had cleaned it all up, but the Venice West Café was still there. So having read the Beat poets and that stuff in high school, I went straight to the Venice West Café in search of the door to the underground. And I found it.

The Venice West Café, as you can imagine, was a pale shadow of itself. But you could sit there all night and drink coffee and someone would come in and read poetry and you could play a game of chess and I know I picked up a couple of girls out of it. And so on. By that point I had run away from home. The family had settled into a house in the Palisades, because my stepdad was working down in Santa Monica. So it’s from Palisades that I’m riding my bicycle down the beach to Venice.

It’s there that I meet Vaughn Marlowe, who was the news director for KPFK-FM in 1964. And he drags me out of there and puts me to work at KPFK as a newsroom volunteer. I was 19. They had the old-style teletype — clackity clackity— where your job is to rip off the copy and staple it up on 8 ½ by 11 sheets and make a script for a newsreader. At the end of November, Mario Savio comes to town. It’s the week between the first speech and the second speech at Berkeley—Free Speech Movement and all that—and he comes down to L. A. to drum up support. So he’s talking to everybody. They give him to me to interview, which basically means to turn him on and stand back! [laughs] Let Mario go! I was just a deer in his headlights. I transcribe the whole thing, trundle it down to the Los Angeles Free Press, and it’s the headline for the L. A. Free Press, under my byline, for Issue #4 [Dec. 4, 1964]. At which point I start working for the Free Press. I’m working both at KPFK and at the Free Press.

I blundered into all kinds of shit. There was a guy working for KPFK named Leonard Brown, he was like an independent producer. I was told that he was the guy who had produced 77 Sunset Strip, which was just the coolest thing on TV in its time. He put together an audio documentary called ‘Five Nights in the Ghetto.’ This was in the late spring of ’65 [actually Fall 1964]. Sends me down into South L.A. with a tape recorder and addresses and leads of people that will talk to white people and explain what it’s like down there. L. A. Free Press had done a big ‘Save the Watts Towers’ thing, so I was aware of all that stuff. So he puts this ‘Five Nights in the Ghetto’ radio documentary together like two months before the L. A. Riots blow up in ’65. I went down there one night with a photographer, trying to find the action, and we found enough action to get rocks and shit thrown at our car. And then the police threw us on the ground [laughs], at which point we ran back up into the hills.

Where were you living at this point?

I was crashing with some guy in Venice who I later realized was chicken-hawking after my tender flesh. Then, when I went to work at KPFK, Vaughn rescued me from that and got me a house-sit for a guy I never met who was apparently off doing Freedom Summer ’64. Then I got some kind of funky little room in Echo Park, Echo Park Boulevard.

Mostly everything that was interesting and the least bit avant-garde (as they spoke of it back then) was being funneled through the L. A. Free Press. Everything was passing through us. So when Ken Kesey and a busload of Merry Pranksters came down to town to show off the Acid Test, we got hooked up with him and we went out. First he did a non-electric version of it, with all the media but not the acid, out at the Northridge Unitarian Universalist church. Looks like an onion, beautiful building. And then the following weekend they did the real one down in Watts—THE electric kool-aid acid test.

Were you there?

Oh yes.

Were you on acid?

Oh, big time. Fuckin’ A. Well the story goes, and I got this from one of the Pranksters, Paul Foster, that they’d dropped a decimal point in calculating the dosage. [laughs]

I was already experienced by then. It was still legal. The stuff that was coming up… You’d go into a pharmacy in Tijuana, you’d get a little test tube, pure Sandoz, over the counter. 250 hits, or 500 hits, or whatever it was, in this one little thing. We did a lot of it there for a while. Started out with Egyptian Book of the Dead lore and went on from there. It became all just about sensory overload. We would go at dawn to LAX [Los Angeles International Airport] and park right there where the jets first hit the runway. [airplane whoosh sound] Pure sensory overload. And then we’d stare at the sun. Shit like that. I have a burned out spot in my eye from it. Or we’d go run around naked all day in the hot sun, out in the hills behind Malibu. I’d never get a sunburn. Funny stuff.

Was your family particularly liberal?

My mother definitely was. She was part of a little scene when we were still living in New York. She knew artists and writers. My stepfather, not so much, and he spent the last years of his life blaming me for the dysfunctional mess his family had become.

What a childhood you had! Living in Manhattan, then in the exurbs in the woods, then landing California right when you did. And being near the birth of big-time TV all through that.

It seemed like I was living in a movie where all this extraordinary stuff kept happening, and I kept meeting people, and just being there, just blundering into the right place at the right time.

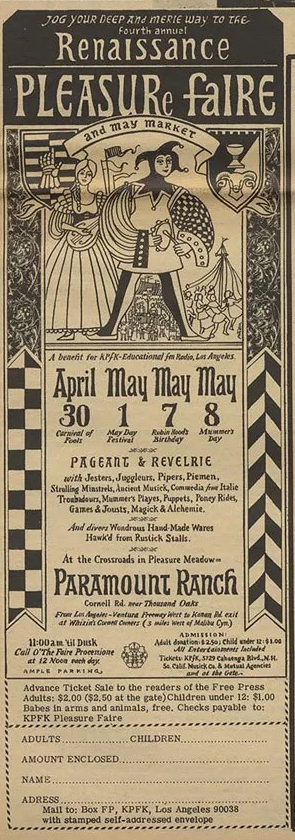

There is a moment… I guess it was the first Renaissance Pleasure Faire, or maybe it was the second. It was promoted heavily through the Free Press. They’d rented the Paramount ranch, where they used to make movies. That was the first time I experienced “liberated space.” At that point, L. A. was full of what we would now call “hippies,” living in their little enclaves of Sierra Madre Canyon or up Topanga Canyon or any of 20 other places you can think of, making their jewelry, their little crafts or whatever. What the Pleasure Faire did was bring all of those people together in one place, at one time. And everyone was in costume. And there were no cops there. People were rolling up joints of innocuous herbs and then of course we were smoking real dope too. Alright! So all these freaks got to see how many of them they were, and what it felt like to be in that kind of liberated space.

I know that that is a very seminal event in that sort of consciousness that was evolving there. It brought people into a bigger picture. Because what I remember about L.A. is: you could go hungry in L.A. It was everybody doing their little thing—there was no sense of a larger scene going on. What really brought that home to me was when I got up to San Francisco and I started to hook up with the first of the Digger people, and someone said, Are you hungry? Just like that. No one had ever asked me that before.

That became a thing we did consciously in San Francisco, as Diggers. It was almost like we had to invent community, because none of us had come out of one. Alienated suburban kids, yadda yadda. And out of that grows ALL of this stuff: the communal living, the crashpads, free food in the park. All of that. Creating your own reality. Live the reality you want. Make your own space. Do your own thing. Create your own rituals. That’s what was going on with all of us. We were inventing this. It was very exciting stuff.

Looking back, it amazes me that I wasn’t in San Francisco for more than a year, and yet that year was like being in a war for a year, in terms of the level of psychic energy and intensity of living, 24/7. Not to mention everybody’s taking dope, all kinds of acid and stuff, to heighten that. It was a real eye-opening thing for everybody to see this grow —the Diggers nurturing this whole sense of community, and the larger picture, and then also trying to answer the big question: When all of these kids come to San Francisco with their flowers in their hair, where are they gonna take a crap?

Backing up a bit: the 1966 Ren Faire: how big was that? Hundreds of people? Thousands?

Hard to know. Definitely hundreds, in terms of people who were displaying and performing there, as opposed to visitors, but the ones that were part of it? At least hundreds.

How did you exit L.A.?

Under duress. [laughs] At that point I had hooked up with H’lane, who would become the mother of my two children. She was in L. A. also. When I met her, she was the receptionist at Elysium Publications. They put out slick glossy nudist magazines. Pushing the envelope of what the postal service would deliver. She was ten years older than I was, so she’d already been around, but more of the Hollywood hipster scene than the hippie scene. I was her vehicle to transition into the hippie thing as opposed to the Hollywood hipster, cocktail waitress, yadda yadda…

I fell in love. We wound up, both of us, working for Art Kunkin at the Free Press. We were salaried by Kunkin, the two of us together. She was just a sort of general fill-in, do little column inch here and there called ‘trivia’ just to fill in the space. And I was the so-called advertising manager. We were actually making enough money that we got a place in Topanga Canyon, which some band — maybe Canned Heat? — wound up in later. Anyway, Kunkin sent us up there to San Francisco in the summer of 1966 to do sort of a “what’s happening in San Francisco” thing. We did the Upper Grant Street Art Fair, kinda wandered around, picked up on the scene a little bit.

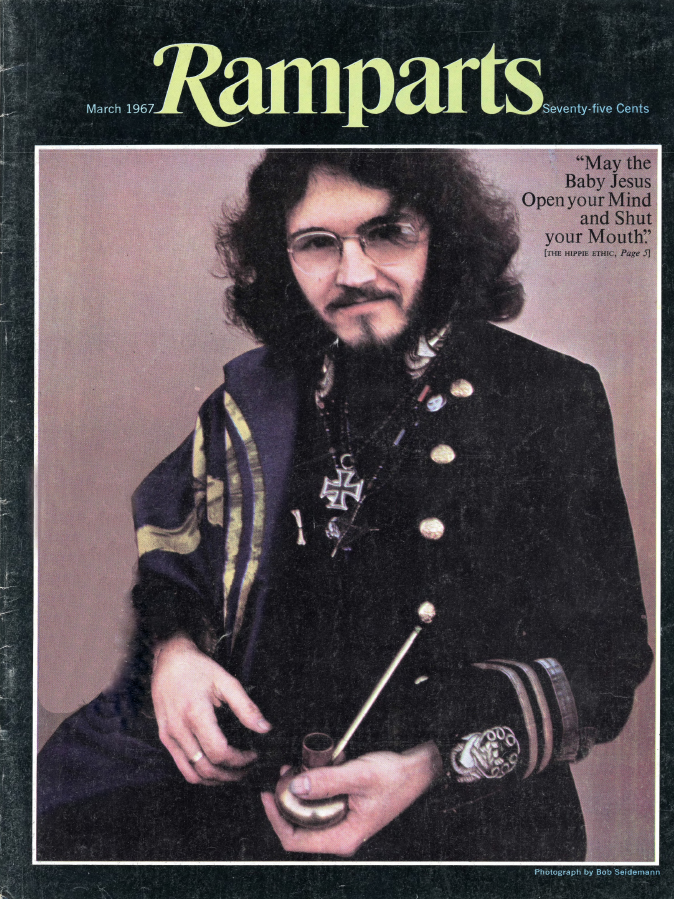

Then we went back up, in another month or two. I ran into the first issue of the Sunday Ramparts, Warren Hinckle’s publishing conceit done in big format. It wasn’t lithographed — by god, it was rotary web press! It was printed in the odd hours at the Chronicle’s press. I managed to walk in there in their office on Broadway and on the strength of my resume as “advertising manager” [laughs] of the L.A. Free Press, got myself a paid position as advertising manager of Sunday Ramparts.

So I’m working there when I start to bump into and discover this Diggers thing. I remember it was [Free Press columnist] Doc Stanley who first brought me over to one of their spaces… not sure which one it was, probably Page Street, the first Free Frame of Reference. Doc said, This is something to pay attention to. It was just, like, a garage. It’s a space. That was just a block or two up from the Panhandle.

I cannot remember how we hooked up with Chester Anderson, but we did. Which turned very quickly into getting the Gestetner machines. The first of these Digger broadsides were starting to appear…

You remember seeing them?

Mmm hmm. Yup, we would go up and down the street and if some guy that looked like you or me handed you a piece of paper on the street, you were gonna read it. This was HOT media. FRESH. You’re gonna read it. It’s not something from The Man.

Billy [Murcott] and Emmett Grogan were doing them out of the SDS office next to the Mime Troupe...

The timing gets hazy in here. The sequence of stuff. I know I went by the Mime Troupe office at some point. Sunday Ramparts had hired the Mime Troupe. Harvey Kornspan, who was the business manager at the time, hustled me up with this idea of, Let’s put the Mime Troupe in costume and go Christmas caroling to all the offices of the big advertising agencies and hand out the rate cards with this sort of entertainment thing. So that’s what we did for a day. I can’t even remember which of the guys, who was on that thing. So there’s that.

Again, it was one of those things, being right there at the right time. I mean, I was there when Eldridge Cleaver got bailed out of jail and got a job at Ramparts, right? He was the office Black liberationist and I was the office hippie, the kid hippie. I shared an office with [future Rolling Stone publisher] Jann Wenner, who was the rock ‘n’ roll editor. He was Ralph Gleason’s protégé, up and coming. We had a tiny little room with two desks in it. I had a salary from the Ramparts, I was still working there in March ‘67 when the hippie issue came out. And there were a couple later issues before they finally gave up and closed the Sunday Ramparts and I was out of a job.

I have a pretty clear picture of what Billy looked like then. But I can’t tell you how I met them, I can’t remember the circumstances, I can’t remember how I met any of those people. And of course as soon as we had that press they were just all over us. That was our gateway into all of that.

How did you guys fund it?

Chester’s book, The Butterfly Kid. It was the proceeds from that book that gave him the money for the down payment on the Gestetner machines.

I have no idea how we ran into Chester, but we did. He moved in with us. He knew about the Gestetner. Don’t know if he knew about the Gestefax. But he had some idea to get a press. The actual receipt for the Gestetners exists. I think they may have let us walk out of there with the printer itself, kind of on approval… and they didn’t have a Gestefax to deliver yet. And then a couple weeks later we got that.

Communication Company was the blog of Haight Street, in the sense of discussing it all. It was almost like a meta discussion going on, right in the midst, and it had that immediacy, that nowness. Commenting on something in the midst of it happening.

Cases of paper would show up. The one bottleneck was that we had to come up with dough to buy the ink. You could only get the ink in the little tubes from Gestetner. You couldn’t just buy ink in another format.

Chester moved in with us. I had just gotten the job at Ramparts and started getting checks. We had been living in just a total fleabag place. Somehow we talked somebody into letting us stay in his building—we were gonna fix it up and all that shit.

Chester was about ten years older than I was. He was definitely more sophisticated with what was all going on… Plus he was running on overtime all the time. Speed, constantly. Chester was pretty ravaged. He was a major speed freak. I tried to keep up with him for that mad couple of weeks where we ran around and did all of these interviews and stuff, putting the Ramparts “Hippie” issue together. It was like CRASH and BURN. That was the sum total of my experience with amphetamines.

Chester had been around: the Village, science fiction novels, back cover notes on a Holy Modal Rounders record. He had a thing going on in New York, but now he switches coasts…?

We had that impression. I don’t know what he had been doing prior that primed him to come to the Haight and have the idea to do this. What I’m remembering is that he… I think I saw the scars… I think he claimed that he had had a lung removed for something, Maybe it was cancer, maybe it was something else. He had gotten very seriously ill. This was before we met him, so he was still in recovery from that.

But why he was not in New York anymore? I don’t know. Maybe he was just sniffing out the scene in San Francisco? Cuz what was coming together in San Francisco was not coming together anywhere else yet. It was still the beatnik roots. The word “hippie” didn’t exist. What is that great line in the “Death of Hippie” broadside? “Hippie, beloved son of media.” They had to invent a word for it because there were more and more people running around looking freaky. I mean, the Beatles were a real inspiration. They let their hair grow long. I remember walking with my tape recorder, a little white boy, trying to look decent, but I still had my hair down around my shoulders, and there were black kids following me up the street saying, Look it’s a Beatle! It’s a Beatle! [laughs]

How did you deal with the draft?

I had been called up in L.A. already. In ’65. I went down to the induction center in downtown L.A. I had long hair, and there was a warrant out for my arrest for jaywalking on Sunset Blvd. Their standards were too high at that point so I was declared ‘morally unfit.’ And so I never heard from them again. It was that early.

You lucked out.

I did. I definitely did. No question. I lucked out so many times, man! [laughs]

Regarding Chester: I dwell on him because he’s kind of mercurial, in addition to being gone, so I’m always trying to find out more. Some of his signed Com/Co texts are really strong.

It’s interesting, because I was reading a bunch of that stuff lately. Chester was always doing the I Ching. Chester was paranoid. “Ah, the Man’s gonna come and get us,” and this and that and the other thing, over and over again. Reading them now, I think he was over the top with that. But a bunch of them are very generous, very good-hearted stuff. He’s giving out advice. He seems to have taken on a feeling of responsibility for passing on info that he genuinely thinks would be helpful to people.

Do you remember his “Uncle Tim’s Children” broadside? That’s an infamous riff, gets quoted all of the time. Do you think he regretted writing it?

I’m sure he never regretted it a moment. I just don’t know that the situation was as bad as he described it. I don’t know. My personal experience is nothing bad ever happened to me, or close to me. It was never a scene of horror for me.

I’m definitely onboard for the whole notion of the Haight Independent Proprietors figuring out how to make a buck out of the culture, which was obviously anathema. That was how the Thelins—Ron and Jay — made it into the mythology, cuz they heard what the Diggers were saying, and did something, did what they could to push things forward positively.

What was your relationship with Emmett?

Emmett was sort of larger than life. Emmett quickly learned that I was sort of the ‘can-do’ kind of person, which has always been the role I’ve played in all of these situations. I’m the guy who’s good with his hands. I had the tape recorder so I get taken along on a trip, etc. I drove the truck. At some point he decided he was going to shoot an arrow into the door of Warren Hinckle’s house, and I knew where it was. He was pissed off at Warren Hinckle for some reason. I remember writing ‘the vagabond that’s standing at your door is standing in the clothes that you once wore’ on the arrow, and we drove by Hinckle’s house by night and Emmett [laughs]… it was just a wooden door, so it would stick there. I never heard anything back about that.

It was always just really exciting. When Emmett came around, it’s like the whole energy level in the room went up, because he was living at a very intense level.

If he came around with something he wanted printed, would he type it up there, or would he have it done already…?

He would usually bring it in. He would just bring it to us. Once we had that press and you put that first sheet out, they were right there.

So then you’d just run it off. How many, a couple hundred?

Depended. Yeah, minimum run. The way it would work was some guy has a poem he wants to share. We’d give him a hundred copies, and he was out. The Gestefax made it possible. This was cutting edge stuff. You could walk in, and 40 minutes later you were out the door, with copies. And, y’know, GOOD copies, too, especially with the Gestefax. People started playing with that. I was playing with multiple colors and working out registration, which is very crude on a Gestetner, because you had to have a different stencil for each… it’s like a three-color process. The first stuff that happens is you start to see the color change across the page, horizontally, because you’d have a color of ink in there and you could unscrew the tube out and put a different color in and it would start inking. The color would shift across.

It wasn’t too long before other people started playing with it. I know at some point, and I think I’m already gone at this point, Billy Batman starts to play with this stuff, and starts to do some real interesting things. Much slicker looking stuff than we were doing.

You’re already gone by late 1967…?

We get out of there pretty early on. At some point we get, y’know, ‘urban apocalypse vision,’— we start thinking, if we just had a little piece of land where we could build a house… All that sort of stuff. I remember building a scale model of a house out of toothpicks and modeling clay. I’d never build a house out of anything, but the bug got on me.

Anyways, Emmett would just sort of blast through. It never seemed like a long period of time. He was always in motion. And really operating on a whole other plane, it seemed to me, in terms of a larger consciousness. I’m just real aware of how young I was in the midst of all that. I’m in the middle of all this, but not really seeing the larger picture. But at some point in there Peter Berg shows me the Gerrard Winstanley book. That’s my St. Paul on the road to Damascus moment, where I read the accounts of the constable that was sent out. ‘Who are these people digging up the commons at Notting Hill and please report back’ and all this sort of stuff and I’m reading this and going, Holy shit! This is the same stuff—it’s 350 years later and we’re still hassling about the same stuff. That was a moment for me because it suddenly put it all in to this very long context.

I’ve always seen Berg as the dialectician. He was the one who had the rap together. I’m still thinking about stuff he made me think about back then. I’m still trying to articulate utopian visions because of him.

Also, simultaneously arising out of all this, you could see the coming cybernetic revolution: “All watched over by machines of loving grace.” The point was that machines were going to liberate humans from slave drudge labor. And so what are the humans gonna do? Well, y’know: they’re gonna do their thing. As opposed to having to be locked into that wage-slave situation. And lo and behold, that’s exactly what happened, EXCEPT that the robots basically are now what were the slaves 300 years ago, and they’re owned just like slaves were owned, and that ripped off energy was for the benefit of the owners. And that’s EXACTLY what we’ve seen—the entire benefits of the cybernetic revolution have been vacuumed off into the pockets of the wealthy. All you have to do is look at those charts of who made money over the last 30 years—us down here on the bottom just flatlined, haven’t had a raise in 30-plus years. Meanwhile the concentration of wealth has just kept on going. How do we value humans in some way other than how much they can sell their labor for? And that’s it. We’d been seeing this coming since then. The handwriting was on the wall 40 years ago. And some people read the handwriting and thought it meant get all you can while you can, because the party’s almost over, and that’s what they’ve been doin’.

Looking back now, do you think the emphasis on anonymity, and no leaders, helped or hurt the Diggers’ cause?

I think everybody took seriously the notion that nobody was in charge. I wasn’t aware of anybody making the move like they were the boss. Now there was no question that there were some strong personalities and ones not as dynamic, shall we say… It definitely had something to do with the quality of rap that you could lay down. But there are plenty of people that were anonymous Diggers that we don’t know of, that were doing one thing or another, either in concert with, or entirely independently. That’s the essence of “No Leaders/Do YOUR thing.” All I’m saying is that I felt that that was honored, that that was respected as a dynamic.

The other approach was Abbie Hoffman, the Yippies, who took the Digger ideas, was all about doing press, being a very public leader/spokesperson.

He put a real political thing to it. I saw him as less of a ‘social revolutionary.’ Because the stuff the Diggers were working on that I thought made it significant was that they were concerned with the society going on right there: the hippies, the community…

The media was always trying to get someone to talk to them about the Diggers. They did try and track us down, to find the “leaders.” I remember at one point Nicholas Von Hoffman was at Coyote’s house talking to a bunch of people. There were some others. And of course Joan Didion found me. She misunderstood! That’s the ultimate joke, because she brought up “media poisoning,” which is one of Berg’s terms, right? And the media thought it meant that we couldn’t talk to the media because we would be poisoned by them. They didn’t understand that what was going on was that we were poisoning them by turning the tables, by getting our stuff out into the public’s consciousness [through them]. But yeah, there’s that one little incident in “Slouching Toward Bethlehem.” She was trying to find Emmett Grogan, of course. [laughs] Everybody wanted to find Emmett Grogan! That whole incident was just five minutes in the park.

So there wasn’t actually a resistance to speaking with them but no one was going to stand up and say yes, I’m the leader. That was a common thread to it. But [we] were certainly willing to explain what was going on to anyone who was interested in hearing about it.

You mentioned “All Watched Over,” which is Brautigan. You guys published some of his work.

Well, he came in, first of all, with the broadsheet. Then we did the whole book, All Watched Over By Machines In Loving Grace, in the original edition, with that bright orange yellowish paper, and the black and white image printed on, Richard looking through the window, on that. That was the first run of it. Apparently there was another run done somewhere else on a different press.

Plant This Book, we couldn’t do because we couldn’t figure out how to get the envelopes through the machine, which is what he wanted, was a seed packet. So he found someone else to do that.

People were always walking in. R. Crumb walked in one day, lookin’ for someone to print the first issue of Zap Comix. Had it all written out, all camera-ready copy. He was looking for somebody to print it in a comic book format so somebody could sell it. But by then we were all into our free press business, plus we couldn’t handle the format. So I had to tell him to try and find someone else to do what he wanted. He did a poster for us for Bedrock One.

Who was Willard Bain? You published a whole novel, Informed Sources, by him.

Willard was working for I believe the Associated Press, and he was pretty crazy. His youngest child, infant Chardin was a crib death and he was seriously bent by this. He wrote this novel. The format he had in mind was tear-off sheets from the teletype machines. Everything that came in the teletype machine that day: Day East Received. At that point he was willing to give it away for free so we printed 500 copies of it. It was put out loose, in an envelope. We sent a copy out to every member of the underground press and as many critics as we could, which got him rolling. [looking at Doubleday edition] This is reproduced directly from what we printed. He gave it to us in this format, of loose sheets. I guess he got the dough to get the paper together to print the whole thing. Five cases of paper. 500 copies. 150 pages. A lot of paper. We printed the whole thing, collated the whole thing— had a big collating party one night, put it all together. It took off.

It’s basically an allegory of the killing of Kennedy. That’s who the character Cock Robin was. That’s very early media meta. We put a bunch of copies in bookstores. Gave it away for free.

Who designed the Com/Co stamp?

“ComCo/UPS”: that was me, as I remember it, typing that line out, that was after we hooked up with that underground press meeting out in Bolinas that Michael Bowen organized.

Do you remember anything about the Invisible Circus?

What I remember of it is that I spent most of it down in the basement running the machine while everyone walked in and had stuff printed. I hardly got out into the scene much at all. I remember Freewheelin’ Frank sitting right there and typing out a poem and then we printed it.

Chester was gay? Bisexual..?

Something! He brought young men home, and disappeared them into his room and I’m sure did unspeakable things with them, but nobody ever said anything about it. There was no mayhem. He was not a violent person, but… I remember being aware, it was sort of my first close-up experience with someone doing a lot of speed: vibrating, quivering. I just wouldn’t go there anymore. There was that weekend where we ran together—again, because I had the money, right? I had the job, so I had the check, so I had the dough to go score. Chester would hit us up whenever he could. He was out of money at that point. I don’t think there were any more royalties from Butterfly Kid coming in, he’d kinda blown that on the machines.

And he didn’t have a new novel on the burner, an advance…

[No.] But he would sit in there and just type away and chew on his tongue.

Brautigan did speed too, I guess?

I wasn’t aware of that. Brautigan hung out with H’lane more than me. I’d be devilling away in the machine room and they’d be chortling away in the kitchen. They connected, somehow.

So you guys left the city…

H’lane and I leave the city in late ’67 but we keep coming back. Every few months, hit the town, get our psychic batteries recharged, steal everything we could and go back off into the mountains. But in the course of those expeditions we’d hang out with everybody. I remember one time I’m walking from the high end of Haight Street all the way down this way and there’s David Simpson walking down Haight Street with a shotgun on his shoulder! I don’t remember if it was broken open or not. And I’m walking with him, and he’s just walkin’ down the street carrying the shotgun, not in any threatening manner. I remember I was like [gasps]. He was just being very cool and easy about it. Nothing happened, which surprised me. I was so horrified by what I saw as the risk he was taking.

Even before we left the city, guns started to emerge. The Diggers discovered guns. So-and-so would get a gun, and then we’d all check it out and they’d go off and shoot it somewhere. There was all kinds of cross-fertilization going on. The Panthers. And you had the Angels. Two MAJOR cross-fertilizations. Coyote and Fritsch and those guys are running with the Angels!

Such a mix of people around the Diggers: the Angels, the Pranksters, the old Beats, the Mime Troupe, the Black Panthers…

All those guys are coming through. They all came through to get their stuff printed, one way or the other.

The Panthers couldn’t find anywhere to print the Black Panther newspaper so we ran off the first issue of it on the Gestetner. There was two guys in uniform. I’m not sure who it was. Could’ve been Huey —one of those guys. I can’t remember. But they came by and we said sure. I was later told that when they took their guns of and put ‘em on the table in their holsters, it was a sign of respect. It was very poor quality, not at all like a newspaper, but they were happy.

Did you have much contact with the Grateful Dead?

They were the band for that acid test in Watts. They were quite accessible in the Masonic Street house, while they were still in the City, before they moved out to Marin. I guess we went and hustled them one time for money because that’s what we were always having to do. We always had our hand out for paper, ink, whatever.

Were you part of the hustling for money down in L.A.?

I never did that. There was a whole crowd that starts to go off into outer orbits. Okay, here we are fetching the bowl of food for the free food in the park or whatever, but they were sort of out there, going international. So we’d heard various stories of that, but again, I wasn’t a part of any of it.

At one point, though, I got next to Bill Buck, who was a wealthy family scion and was a philanthropist, and I laid the whole Digger rap on him about urban apocalypse and places of refuge and you have to have a place in the country for people to be safe and learn the old ways et cetera. He said okay, and so we went and found our piece of land. This is pretty much concurrent with the Black Bear people doing their thing, and the Diggers evolving into this Free City thing. But we didn’t hook up with any of that. In fact, we probably had the Land before Black Bear got theirs because we bought that land in late ’67… In Covelo, northern California. It’s right up there where Mendocino, Trinity and Humboldt counties all come together. That was land that was going to be liberated — land that was removed from commerce, [in the words of Morningstar Ranch founder Lou Gottlieb] ‘land the access to which is denied to nobody.’ It was a whole Digger thing.

I was all excited, whoa—cuz this was my shot. Because within that Digger subculture, it was almost like in the old potlatch culture: the more you could give away, the bigger Robin Hood you could be, the more you could provide, that was how you achieved status. So it was very exciting to me to come into my own, because I had been sort of peripheral to a whole lot of other stuff going on.

What was ultimately disappointing is that nobody came! We had this place — and nobody came! Couldn’t talk them into it. That was PRIMARILY because they were all by early ’68 focusing it on their Black Bear thing. Black Bear is ANOTHER almost 200 miles further north than WE are. Same range, but further north.

Kent [Minault] talks about stealing wood out of Diamond Heights to be used up at Morningstar…

We did the same thing. We organized raiding parties. We got the ferrocement dome bug. We’d read about ferrocement in the Whole Earth Catalog. It’s a high concentration of reinforcing steel, very finely divided, with a very rich, high grade concrete mixture. Done properly, you get incredible strength, very thin. So. We were gonna do that, we organized a party one night and we came down… We rented a giant U-Haul truck, went to one project after and loaded a bunch of rebars in, went somewhere else, a load dock, and rolled a couple big rolls of quarter-inch wire and then we wound up on Market Street at 2am on a Saturday night, just as the bars are letting out. And Market Street is of course all torn up for the BART. And we drive right in, pull in to one of these enclosures in the middle of Market Street, we all have hard hats on, throw a couple hundred bags of ferrocement in.

This is us at the land doing our thing in the Digger tradition. Pursuing our thing. You get very provincial out there, it becomes very us-and-them, as in we’re the only ‘authentic’ people because we’re tough enough to live out here and make it like this. Thus everyone else is fair game, right? The gypsies come raiding out of the hills. It all seemed perfectly legitimate to us.

And Black Bear did the same thing. But they had just a whole lot more energy, which is why they were able to flourish in the way they did. I literally wound up… in 1968, we go to Wheeler’s Ranch in our Army truck, which is like the overflow of Morningstar, literally cold-call, looking for settlers. [chuckles] We got two people.

Had you been part of those Diggers expeditions out to New Mexico?

Nope, I wasn’t. Emmett went. And I think Coyote went. I think they both hooked up with one of the Littlebird brothers, Larry Littlebird. Native American poet. Emmett came back and he had ‘gone hunting with them.’ He had a rifle. These of course were all new worlds opening. None of us had ever hunted or any of that kind of thing. And then there was the great expedition to go get wheat for the free bakery—wheat to grind into flour. They were gonna go get hard red winter wheat somewhere in Colorado. I wasn’t on that trip either cuz we were up in Covelo but we heard about that trip. And somehow out of that trip some of those people wind up in Huerfano Valley next to Gardener, Colorado. And some of them are still there.

The last interaction we all had was that great gathering at Black Bear Ranch in the fall equinox of 1970. That’s when I met Ben Morea. He and his crew had blazed their trail to New Mexico that year. The so-called psychedelic cowboys—the [Up Against the Wall] Motherfuckers’ crimewave spree across the country had wound up in New Mexico. And in fact, my family now owns the places that they occupied. And then Ben and Chipita, his wife, and Berry Spiegel and his wife Laurie Spiegel known as Redhead Laurie, made it up to Black Bear Ranch. They saw themselves as allied to, or of the same stream as the Diggers. That’s where we got the New Mexico bug. That’s why we specifically went to New Mexico. We were gonna go on horseback and be ‘free’ in the wilderness and blah blah blah.

I was severely bent by all that. It was another ten-plus years before I came out of the hills. In 1978 I left the mountains and went to town [Albuquerque] and got a job, to take care of my kids. That was basically what precipitated it. And the whole scene—it was especially provincial up there in New Mexico, it just got to be too small a world. I started getting exposed to a larger world, and experiences that no one up there could relate to. I re-entered the world. But in the course of doing that I discovered just how much I had learned being out there. And I’ve always seen myself, and this is true of many of us, as, we went way, way WAY out there. Some of us didn’t even get back. Some of us came back damaged. But, you know, in some sense, I’ve always felt, being back in the world, that I am manifesting what I learned there. Which is why I’m a broke poor hippie, age 66, because I just couldn’t relate to money. And yet people would want me to do things for them, like, Can you fix my truck. And I’m always, Oh yeah I can do it! I’m Mr. “Put Me In, Coach, I can do it!” Story of my fuckin’ life. And yet I don’t need any more chickens or a basket of apples. Okay, I could use this money… But money was magical, somehow! At least for me, and I know it’s true to others, it manifests in this totally outrageous act, of BURNING THE MONEY.

I’ve done it a couple of times and it’s very spooky…

It is powerful fucking shit, yeah. Then you start thinking about it. I think about it in terms of, Alright I go out and hump a wheelbarrow all day and work my ass off. And what comes out of it is this piece of paper. Now, the work was real. It happened. But if I burn that piece of paper, it didn’t happen.

Anyway! I sort of had to re-invent the whole business for myself, conceptually, to come to a place where my moral integrity was intact to accept money for my services. I had to build my own integrity. You go to Coyote’s book and I’m described as a master thief. And, I think I was, at one point. We were convinced if you ate enough ginseng, you could slip right through. We could steal ginseng from the Chinese herbalist… H’lane was really into it, and she alienated a LOT of people. She was also too much for me. The thief that becomes a person of integrity takes pride in making a deal, making a handshake deal — that basically saved my life. The notion not of getting a job, but finding my work.

The stuff we dealt with wasn’t—for me, anyway—an abstraction. I was shaken to the core by this stuff.

Shellshocked.

Well, right. But then I somehow re-assemble, put together a life in the real world.

The Diggers were different than other ‘60s figures: not protesting, not making demands.

The activist’s whole identity is tied up in him being denied, as opposed to him manifesting. Nobody can give you your freedom. You ARE free. It is your natural state, okay? You can give it all away if you want, but: no. I can’t GIVE you your rights. I can’t give you your freedom. And to go and beg the Man for your rights and BEG the Man for your freedom? LIVE your freedom.

One of Berg’s phrases was ‘life actor.’ ‘Theater of the streets.’ All of this as theater. As opposed to in a different arena you would call politics or activism or so on. But using theater as a way to open doors that might not be opened if someone was approaching it in other ways. Out of that comes this whole sense of ‘create the reality you want to live in.’ Which is a powerful, profound concept. People are trapped in the paradigm: you can’t even think there is an outside of the box. Just that notion of thinking, and living outside that paradigm, was real powerful stuff.

Well, we think now, ‘Of course.’ But 40 years ago this was like, Whoa. A powerful concept. [Right now] “Occupy” is creating a liberated zone. Back to the same thing. All we can do, now, with our perspective is recognize the long tradition. The chain continues. All the way back to Winstanley. And it didn’t start with him.

We all dropped the ball, in some way.

Do you think it was that close?

I don’t know. All I know is they sure have managed to consolidate their power in the last 40 years. We were operating within the interstices of this very open society, and it was just rife with opportunity. It was so wealthy. There was all this stuff laying around. Free food. Gleaning! That was a powerful thing for me. When somebody knew somebody that had a zucchini farm and we’d go out there and bring back a truckload of zucchinis. I went on a bunch of ‘em. There were multiple occasions within the Digger context here in town but then we ourselves on our own did that for years afterwards. We knew where there were almond trees, where there were fig trees, abandoned orchards. Or you go to the tomato fields at the right time. We literally would set up a canning kitchen by the side of the road and can tomatoes, because there’s no way you’re gonna get them back home to process them. We really ran with that, all based on the structure as set up: the cash economy, the guy’s just sold all his produce and meanwhile there’s still a third of it left in a field waiting to be plowed under to start again. And for the most part those people were like, Yeah sure pick up what you want. They were actually delighted. What farmer wouldn’t feel bad about plowing produce under?

To a greater or lesser extent people outside the Haight tried to manifest what they were hearing about what was going on. Every university town ended up with a headshop. And a scene. Because, yeah, not everyone could get to San Francisco. Of course you did if you could, because it was a beacon. But I think at the same time a lot of people were getting the message that it was universal, San Francisco wasn’t the only place this could happen. Some of these concepts are just universal, like free food. ‘Are you hungry? Have you eaten today?’ Profound as that was for me, it had to have been profound for any number of other people, to be met on that kind of a level of concern: a real basic elemental level. You go back to certain cultures: the concept of hospitality! The traditional Arab culture: some guy wanders in off the desert, suddenly he’s in your care. He’s a stranger, but you are required to extend hospitality to him.

It’s all tightened up enormously since then, in terms of there isn’t that kind of surplus lying around. But at the same time, there is. There’s still enormous wealth if you know where to go. As times get tough, people learn how to do it. We basically all went to sleep for the last three decades, it seems like.

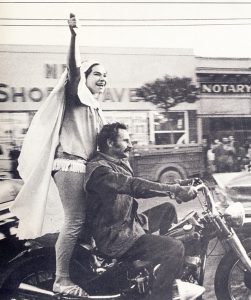

One more thing: you are featured in the famous Kirby Doyle/Diggers text, “The Birth of Digger Batman.” What are your memories of Kirby, and that birth?

I remember one time we were at the Red House. We lived at the Red House for about three months. Our house had burned down—this was ‘69—and H’lane was very pregnant with our son. At some point Kirby and I went into town in my Army truck. It stopped running. I went under the hood and I did something. Then it started running again. ‘A momentary indisposition,’ Kirby called it. I’ll never forget that phrase.

But no, I didn’t actually spend a lot of time with him. By that point he had written ‘The Birth of Digger Batman.’

Later on, I met Digger Batman on his 30th birthday at Redhead Laurie’s house, who was married to Barry Spiegel, who ran with Ben Morea. I’d built their house out in Taos and I guess she was having an open house for it. He showed up with Joanie, his mom—Batman’s widow. I’d never met him before. And he thanked me. Just for…whatever it was.

Top-shelf addition to your Diggers series, JayBab. More evidence that there was a lot more substance to hippies than Cheech & Chong cliches and revisionist bulltrump about everyone tossing tie-dyes to don suits on Wall Street. OK Boomer? Boomer OK.

I eagerly await next installment.

LikeLike

This project is, for me, monumental. Finally someone, Jay Babcock, gets it right.

LikeLike