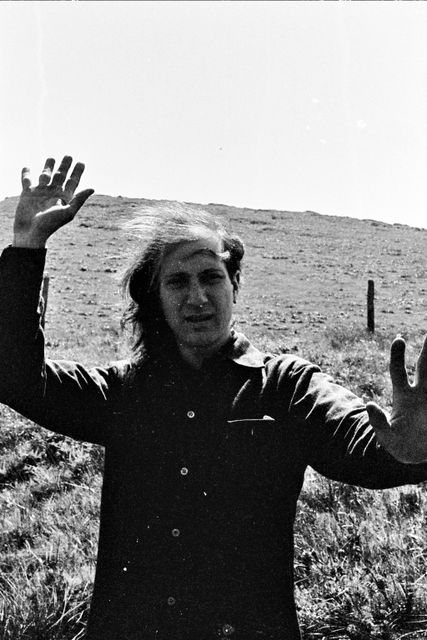

What a joy it was to find Claude Hayward alive and well and ready to reminisce and think about the San Francisco Diggers back in 2011.

Claude was a shadowy figure in the Diggers — mentioned here and there by name in various accounts and memoirs, famously rendered as mysterious and evasive by Joan Didion (!), the one living guy who could talk in depth about the late Chester Anderson, his partner in printing over 600 broadsides (many of them Diggers-penned) as the Communication Company. Amongst Diggers and children of Diggers, wild stories abounded about Claude’s life before, during and since the Haight. I thought he might be hard to find. But he was right there all along, online, active on Daily Kos and easily reached by email.

I interviewed Claude in a San Francisco backyard on October 2, 2011. We were both in town for the public memorial to the recently departed Peter Berg. I think we were eating apples and drinking coffee. We got a lot of talking done; what follows is pretty much how the conversation went, with some edits for clarity, and some later additions and deletions from Claude.

In 2021, the Diggers are little-known. But in 1966-8, such was the Diggers’ presence and notoriety that seemingly every reporter filing a story on the Haight included the Diggers in their account. “A band of hippie do-gooders,” said Time magazine. “A true peace corps,” wrote local daily newspaper columnist (and future Rolling Stone editor) Ralph J. Gleason. The Beatles’ press officer Derek Taylor would write, “[The Diggers] were in my opinion the core of the whole underground counterculture because they were our conscience.”

This is the eighth interview in my series of Diggers’ oral histories; the others are accessible here. For more information on the Diggers, consult Eric Noble’s vast archive at diggers.org

I have incurred not insignificant expenses in my Diggers research through the years. If you would like to support my work, please donate via PayPal. All donations, regardless of size, are greatly appreciated. Thank you!

— Jay Babcock (babcock.jay@gmail.com), October 2, 2021

Jay Babcock: What’s your background? Where did you grow up?

Claude Hayward: My mom’s dad had come over from Germany in 1930; he apparently got a job and made enough money in New York City to bring his family over five years later. Whether he was overtly political or he was just not going to tolerate this crap in Germany and managed to get himself out, I don’t know. He was working class, made stuff with his hands. My mother was born in Germany. She was 9 years old when she got here in 1935. She grew up on Long Island, met my dad at the Grumman Aircraft plant where she and her dad and my dad were all at work building airplanes just before the end of the war. I was born in Brooklyn in 1945.

I lived in Brooklyn in a couple places, then my mother re-married when I was 6 and we lived for part of a year in Greenwich Village, where my stepdad had an apartment. And then we moved out to New Jersey in 1952, some funky place in what’s now called Piscataway, outside of New Brunswick, and I grew up there, that was my boyhood. More country than not—pretty much free to run around, the woods, there were animals to be seen, there was a dairy farmer over the hill and all that. All kinds of Revolutionary War and pre-Revolutionary War ruins and stuff. Apparently Washington camped the Army right there. It was right across the street from Camp Kilmer.

What was your mother doing?

She was being a housewife. I have two half-brothers and a half-sister. They’re younger than I am. My mom took college classes as she could all through her family raising years, and eventually got a degree in English and a teaching credential in German, her native tongue. She was a mighty sharp cookie who somehow managed to impart some lasting values to me.

And your stepfather?

He was a broadcast studio engineer for WABD-TV Television in New York, which was actually the first commercial television station, created by Allen B. Dumont, the engineer who invented the method of mass-producing TV (cathode-ray) tubes that made the explosion of TV into American culture in the early ’50s possible. They were really pioneering stuff. They did Captain Video and Video Rangers live in the studio, 5 o’clock every afternoon. They did other stuff, just taking the camera out into the streets. Nobody had done that. They didn’t know what the fuck they were doing. They were trying to learn how to use this new medium.

So I was six years old and in a fifth-floor walk-up apartment with a shared toilet in the hall. And I had my own television set! With tubes and a screen about that big. My stepdad was the kind of guy that could monkey around and fix it, he had boxes of tubes and resistors and capacitors and all that.

TV was the beginning of the great homogenization of American culture. That’s all you talked about in school: “Did you see Disneyland last night?” Which meant, did you have a television set? These were black-and-white TVs; color hadn’t gotten there for another couple of years. I remember hearing schoolmates talking like what they had heard on TV the night before, imitating the mannerisms and idioms of speech.

We got out of there in ’59. My stepdad got a job to build the educational television station at Michigan State. I was there when they did the first live broadcast of a basketball game. Two semi trucks, with gigantic cables going out across the parking lot, the very first video tape recorders. Big Ampeg machines with two-inch tape. He was in at the beginning of all that. And he went on from there. He built the education television station for Santa Monica City College — KCRW — and he also worked in Las Vegas, put together the educational television station there at UNLV. He moved around and managed to get sideways with everybody and had to go find another job. I think the last job he was doing was working out at the Northridge campus in television, teaching people how to do the knobs and stuff.

He ran the radios for a group of tanks crossing France to liberate Europe and God knows what he saw. He never spoke of it. Came out of it bent, but managed to hold it all together long enough for his family to disintegrate around him as the ’60s crashed through. I, of course, had gotten away from that as soon as I could, by mid-’64.

All my family are builders. We learned that you could just do it. My stepdad got a Sears-Roebuck catalog and converted the coal furnace in the basement of the house to an oil-burning furnace by himself, soldering copper parts with a gasoline blowtorch. And what I learned from that was, Well yeah you just do it! There’s no sense of, I can’t do that, or, I’m not qualified. I think that’s got to be the most valuable lesson I ever had.

Continue reading ““I lucked out so many times, man”: CLAUDE HAYWARD on his life before, during and after his time with the San Francisco Diggers”