I first interviewed Harvey Kornspan in August, 2010, after I had traveled hundreds of miles to interview many other Diggers in the San Francisco Bay Area, Sacramento and further up the coast, deep in northern California’s Emerald Triangle. This was a bit strange, given that Harvey lives in Silver Lake, less than two miles from the Atwater Village bungalow I was rented until 2008. For years I had been researching the Diggers, and there Harvey was all along, just a hop away.

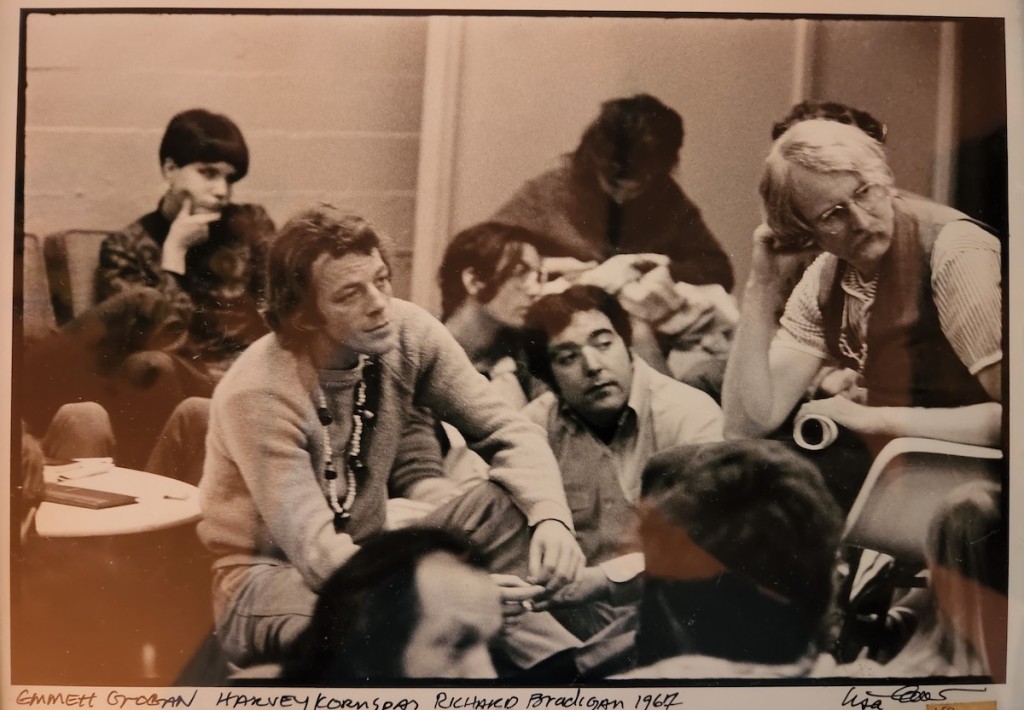

But Harvey was not just a Digger, and he wasn’t just a local. Because unlike every other Digger I’ve ever met or contacted, before or since, Harvey had kept the figurative and literal receipts of the era. So not only did he have his wonderful memories — more of less: it was the ’60s, let’s be reasonable — but he also had unpublished letters, manuscripts, broadside drafts and business documents, as well as a sizable collection of flyers, newspapers, and other ephemera, which he was happy to share. (Some of them are shown here. Harvey is a mensch.)

For the uninitiated: in 2022, yes, the Diggers are little-known. But in 1966-8, such was the Diggers’ presence and notoriety that seemingly every reporter filing a story on the Haight included the Diggers in their account. “A band of hippie do-gooders,” said Time magazine. “A true peace corps,” wrote local daily newspaper columnist (and future Rolling Stone editor) Ralph J. Gleason. The Beatles’ press officer Derek Taylor would later write, “[The Diggers] were in my opinion the core of the whole underground counterculture because they were our conscience.”

So, as the counter-culture came into being, the Diggers were there, the Diggers were important, the Diggers were well-known, but crucially, though they acted in public, the Diggers were anonymous. Nobody knew who they were, where they came from, or how they did what they did. In short, they had a mystique: a group of LSD-fueled street anarchists with a philosophy/practice of “everything is free / do you own thing.”

I recently came across a March 1967 article from the Foghorn, a student newspaper published by the University of San Francisco, a private Jesuit school, that summed up the Diggers vibe succinctly:

The sign on the door said, “You are a digger.” About 50 people had accepted the invitation and moved into the house high in the hills over the Haight-Ashbury.

A cauldron of stew was cooking in the kitchen. The stew, eventually, would be trucked down to the Panhandle, free for anyone with a bowl and a spoon. No one know for sure who brings the food that goes into the stew. Some is donated, some bought, some stolen. The stew would be good today; someone had brought two chickens.

It’s all the work of the Diggers, a mysterious, amorphous group in the Haight-Ashbury dedicated to given things away free and “doing their thing.” They have been evicted from more than half a dozen flats, apartments, and store fronts in the six months of their existence in San Francisco.

One place of refuge is the All Saints Episcopal Church on Waller, where Father Leon Harris has let the Diggers use his church kitchen to prepare the food for the Panhandle for three weeks now.

“The Diggers are industrious, cheerful and benevolent,” he said. “They also give away free clothing and find lodging for homeless people. It seems to me they put a lot of professing Christians to shame by their goodness.”

What follows is a consolidation of various conversations with Harvey, which, to some degree, builds on my previously posted Diggers oral histories, and, as it includes the inside story of why the Altamont disaster happened, offers something of a conclusion. So, many incidents and personages are spoken of without context, or only in passing. My advice to the casual-but-curious reader is to simply let any unfamiliar/unexplained bits pass. Keep reading, you might get something out of the next part.

This is the tenth interview in my series of Diggers’ oral histories; the others are accessible here. For more detailed information on the Diggers, consult Eric Noble’s vast archive at diggers.org

I have incurred not insignificant expenses in my Diggers research through the years. If you would like to support my work, please make a donation in my PayPal TipJar. All contributions, regardless of size, are greatly appreciated. Thank you!

— Jay Babcock (babcock.jay@gmail.com), July 27, 2022

Jay Babcock: Where’d your grow up?

Harvey Kornspan: I was born in Youngstown, Ohio. My dad sold used cars, had a very successful business. Not rich, middle class. Jewish, both sides. My mom was a homemaker. I have a sister who’s four years older and a brother with Down Syndrome.

I was the apple of my mom’s eye. My dad was tougher, but not…too tough. He was quite religious. He was a traditional Jew—he was Orthodox about some things, but he didn’t wear a yarmulke. Kosher house, to the extent that we had four sets of dishes. Two sets of good dishes—two sets of everyday dishes—and then two sets of Passover. Here’s a good example of my dad: If sundown was at 6, we had sundown at 5:30 at our house, just to make sure. And, I don’t know if you know of this tradition, but if a meat knife gets touched by milk, it becomes treif, right? So, the way to cleanse the knife is to bury it in the earth overnight. Well, “overnight” didn’t work for my dad. He’d leave it in the ground for a week. And by the time it was pulled out, it was rusty. [laughs]

My dad frequently carried his own paper. He had clients repeat buying from him all my life. Mostly he sold medium-priced cars. And he’d always have a row of what he’d call junkers, under $200. Transportation, he’d call em. He sold a lot of new cars in order to get the trade. He’d get the car for the customer that they wanted at a price that would allow him to do well in the trade, and they had no residual so everything was clean. He was a good guy, my dad. At 88, my dad sold a car, four days before he died! He was a great guy. And so was my mom.

My teenage years were normal. My friends and I played poker, we rode our bicycles, we marginally got in trouble. I was enamored at the Beats. I graduated from high school in 1958.

You went to university?

I went to University of Wisconsin, in Madison. I was originally going to be an engineer but I never really got the hang of mechanical drawing. I was good in high school, but mechanical drawing in college? Gears are the hardest thing. Every angle, on every tooth is different. I just couldn’t fuckin’ do it! I never recovered from that. So I went into philosophy.

Madison is where I met David Simpson. David and I lived across the hall from each other upstairs. Boz Scaggs and Steve Miller lived downstairs. We ran a crap game several times up in our apartment. That was wild. [laughs] David was a sought after guy back then, a lot of women were attracted to him, so he was good to hang out with cuz I got some of the leftovers. [chuckles] He was way more charming and easy-to-use than I was.

I moved from Wisconsin after college to New York, not knowing what I wanted. Winter of ’62. First, I went back to Youngstown, Ohio to prove to my parents that I didn’t want to be there and they didn’t want me there. They understood that I didn’t want to be in the business. My dad was a righteous dude.

So I went to New York in ‘63. I’d already done LSD and pot at that point. Madison was pretty hip. And it had a good scene—a long, progressive scene. Also, my girlfriend’s roommate’s boyfriend went to Mexico in spring vacation and brought back a bunch of Mexican weed stuffed in the door panels. In 1962, that was possible. He rolled Demetra, that was her name, he rolled her about 20… we used to call them sucker-stick joints? They’re just about the size of a sucker stick, very tightly rolled, perfectly rolled, and gave ‘em to her to take home for the summer. And she lived just 12 miles away in Warren, Ohio. We were great pals. Her roommate was my girlfriend, we were really good pals. We hung out almost every day, in the evening, and one night she said, You wanna smoke some pot? I said, Isn’t it illegal? And she said, Well it is but I’ve been doing it, and Tony gave me these joints. So we went out by the reservoir and smoked some pot. She said, You feel anything? I said, No not really. How bout your ears, do your ears feel a little warm? [laughs wildly] Which I’ve never heard since! And then about five minutes later, I realized things were happening.

I went to New York, subsequently. I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. I didn’t have a plan. So I went to New York to see what that brought. I ended up working Christmas vacation for Bonwit Teller in the men’s shop. I stayed through that. And cuz I need a job, I applied to two places. One was Metropolitan Life. Because by then my ex-girlfriend was doing programming for Met Life. Punch-card, right? So I took their test, and at the same time someone said well the Welfare department’s always hiring. I went and took their test and they said, If we’re interested we’ll call you, and probably it’ll be in the neighborhood of six months. Well right after the Christmas season, probably within six weeks of taking the test, I got a job. I worked in the southwest Bronx Welfare department, as an investigator. Which is a caseworker, really. I had like 80 cases, most of them were Aid to Dependent Children. Most of them were Black and Puerto Rican. And, interestingly enough, I had quite a few Indians—dot, not feather—on my caseload. I tried to be righteous but at the same time, there was a fair amount of abuse, but whatever, I did my gig.

I applied to law school, and I got into Hastings. I came later in the summer of ’63 to San Francisco. I went to law school up until Easter break. I was just floating around, not paying attention. I wrote a letter to the dean, I said I’m not paying attention, I’m not giving it my best, this is not good for me. I would like to withdraw in an honorable way and maybe come back at another time. He called me into his office, he said I’m very impressed, I understand what you’re explaining to me about not wanting to screw this up. So he wrote a letter to the college saying I can return anytime I want. I thought about it when I was in my 50s. [laughs]

Then I worked. I went back to Wisconsin that summer and worked at the Green Ram Theater with friends, who had a summer stock theater. Six plays, maybe eight plays, in the course of the summer, every week, right? People had subscriptions, and it was in a barn renovated into a theater, with curtains that rolled up on the side. A nice evening. It was mostly always open but sometimes it rained. They had training for actors, so the resident company, a lot of them were students. Then there were a few professionals—university professionals I called them, and directors from the university professional area. It was a gas. That was a very free time.

I went back to San Francisco at the end of that summer. Lurched around, went to work for Marin County Juvenile Hall for about six months. I was hanging out in the coffee shop on Haight Street. I forget what it was called now. Everyone had the biggest crush in the world on the main waitress. She was a great gal. So you’d go up there at two or three in the morning, there’d be a half a dozen people, you’d know a few of them. You’d see people like Claude Hayward and Chester Anderson, not necessarily all the time, but it was a big floating… David lived in the neighborhood, I think, at that time? And we just had a big cluster of friends that just morphed.

Now, at this time, the Mime Troupe was a thing that’s happening. And I’m hanging out with David, he’s at Berkeley. Maybe grad school, or maybe he was finishing his undergrad finally…? He’d already been to the Coast Guard. He had a little notion of being an actor, and the Mime Troupe had made kind of a splash because of performing in Lafayette Park. They’d got busted. [Mime Troupe director Ronnie] R.G. Davis kind of set that up. He knew a bust was threatened, cuz they didn’t have a permit. And he pushed that envelope, y’know. They did in fact do a bust, and then he used that as a fundraising tool.

The first thing that happened was there was a fundraising party, in the parlance, called Appeal One, and it was the first produced show to raise money for the Mime Troupe at 924 Howard, which was where the big studio loft was. There was a flyer handed out, which is called Appeal One.

It was great, it was a great show. A group of us went down to this. It was a buck. We went down to the loft and looked out, and there was a line of people that looked an awful lot like us! Dressed like us! It was just scary! Where did you all come from? [laughs] When we finally got to the door, which took a while, there was [Mime Troupe business manager] Bill Graham sitting at the foot of the stairs with a little chair for a bench, and a chair for a table, and he had an Army surplus backpack and it was filled with crumpled up money. I just remember looking at Bill looking at the money and his eyes were fucking spinning, he was like a slot machine. It was unreal. And that was the moment that it all came together. That is the history of San Francisco rock ‘n’ roll. It had transitioned out of the Beat period. When I got to San Francisco, the Beat period was largely over, and the hippie period was nascent. This was the moment that the whole scene came together. I may have things a little jumbled. [laughs]

Right after that, the Mime Troupe had an open call. David said, I’m gonna go down. I said, Well I’m just gonna come along with you. So somehow I got on stage for the thing with Ronnie Davis and Sandy Archer, who was his girlfriend, she was the lead chick and as gorgeous as anyone you’ve ever seen. Fabulous woman. R.G. was impossible! But he had enough of a trust fund that he was the only person in the company who could work for nothing. Not that he had a lot of money! But he could work for nothing. Maybe he was getting, who knows, 500 dollars a month? So, that was the ethos.

David got asked into the company as an actor. Ronnie and Sandy called me into the office and said, Look it’s clear you’re not going to be an actor. But we really need a business manager, Bill Graham is leaving. And I said. Great I’m in. And they paid me, I don’t know, 50 dollars a week. And I did that and I tried to grow the business and whatever. Then the company was gonna go to New York, which it did, briefly, to do a thing called The Minstrel Show. The show was really good. People like Sammy Davis and Harry Belafonte came for little performances up in the loft to see if they would invest or what they thought. It got noticed.

It’s just so funny looking back at the period, the battles. Like the biggest battle in the fucking company at the Mime Troupe was if anything was a success, you’ve sold out. If you have success, you’ve sold out. There would be loud, noisy, pushy arguments about that. He [R.G.] was into purity, which equals “not success.” He didn’t really want to be successful. So, doing the Minstrel Show, off-Broadway, to acclaim? That would’ve been great. And everybody would have gotten their 50 dollars a week, and maybe a place to stay. Maybe not.

Ronnie lived as frugally as anybody, mostly, but he could afford it, he didn’t have to worry about his rent. By calling his folks, and saying I can’t make the rent, I need to borrow a hundred bucks.

That’s when I hooked up in the rock ‘n’ roll business, right after that. Miller was in Berkeley, I went to see him a few times, we talked. I wanted to get into that entertainment thing, and I did. And I managed him, and produced—not physical production, in terms of the sound, what you think of as a music producer. And there you go. [laughs] That was the whole trip to that.

So you were already working for the Mime Troupe when Emmett Grogan showed up...

One day, Grogan, who had just gotten free from service, came down. He was Section 8’ed. He was at Letterman General Hospital, Presidio. He had just gotten out and he came down to the Mime Troupe. He became involved. Wonderful character. We started hanging out really seriously together and I got all the anarchist [spiel]… Grogan was a huge fan, probably partly because of Billy Murcott, of George Metesky, the Mad Bomber. They were kind of a fan of that. Anarchism was always a marginal edge. Of course the Mime Troupe was radical socialism. You get my drift…

Ronnie had allowed SDS to use a small fish office, part of the Mime Troupe’s. They may have paid rent for all I know. Maybe not. And they had a Gestetner machine. An expensive machine. I don’t know that they ever made a payment. I think they bought it on a lease. Anyway, I remember Grogan talking about anarchism and he would rip off or print off something, talk about shit. Billy [Murcott] was around sometimes and various other players. You know the famous photo on the steps. Well, all those people were in the Mime Troupe. Roberto. Kent [Minault].

The whole notion of the Diggers kind of evolved out of the anarchism thing. And also there was more than a little social conscience. Because, by now, in ‘66, people started to come to the Haight Ashbury from all over. And that was when, in ‘66, it was still, really… Before the “Summer of Love,” it really was the Summer of Love. The “Summer of Love” [in 1967] was Life Magazine’s version. That’s what created the homeless on the streets and all that shit, because so many people came with absolutely no understanding of what they were about.

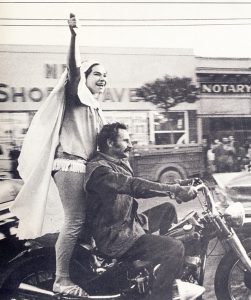

The role of the Diggers in this period was an outlaw, romantic, feed-the-people, anarchist, ‘Who’s in charge?—YOU ARE’, that kind of thing. That line in Apocalypse Now when he gets to the bridge and the little string of Christmas lights are hanging and he gets to one guy who’s guarding one end of the bridge and he says, Who’s in charge here? He says, I thought you were. And that’s so true. That is so true. Then Grogan, whenever anyone would ask, where’s Emmett Grogan… anyone could say “I’m Emmett Grogan.” So you could deflect a lot of shit.

I remember when Paul Krassner came on the scene, just nosing around. He was a respected cat because of his magazine and so forth. But there was a whole bunch of us, we were in the garage, carrying on talking politics or what to do next or just to hang out. Smoking pot, probably. And Krassner came and he said, I’d like to meet Emmett Grogan. I said Emmett Grogan is everywhere. Here. Everyone is Emmett Gorgan. He said No, no I really would like to meet him. I want to give him some money for the work he’s doing, donate some money. And I said wow, I don’t know. Well, you’re welcome to do that. And I knew that Emmett, if somebody gave him money, that he would destroy it. So I introduced them, said Hey Emmett, Paul Krassner wanted to say hello to you, wants to donate some money. And Krassner pulled out a ten-dollar bill and gave it to Emmett. And Emmett took a cigarette lighter and burned it right in front of him. And that was an unspoken set-up, because I knew that was something he would do. This isn’t about DONATIONS! This isn’t about charity!

Where did the stuff come from?

Well, first of all, we were getting donations of all sorts of crap—day-old food, whatever. And there was stealing. Some people, apparently Claude Hayward was really brilliant at just pulling up to a loading dock and taking shit off of it. [laughs] Pulling up to a loading dock and carrying off a slab of beef. And that went on for a while. They were “liberating.” That was always the word: Liberating!

[Examines signed lease for 1762 Page Street garage, “which was the Digger garage.”]

Peter Tytell was one of the mainstays of the Digger garage. He was a footsoldier, one of the younger guys. And he ran it at the end. His father had Tytell Typewriters in Manhattan, was the only guy in the world fixing typewriters as late as 2000, and Peter had taken over the business by then. He was wonderful. I would guess he is still in New York. He was on the ground floor. He was there. He was a real foot soldier, he was the kind of guy that would scramble out of the back of the truck and run up on the loading dock. He was one of those.

My wife and her roommates occasionally made the stew for that day’s thing. One of the best things, and I think it was a Peter Berg thing, I’m not certain but I’m pretty sure, it sounds like a Berg thing, at the time I associated it with him, was the Free Frame of Reference. We’d carry the Frame down to the park, lean it up against a tree and then you could look at reality from either side of the frame.

Who was Peter Berg for you, at that point?

Peter was not just another guy around. He was smart. Really, the Hun was very, very smart. Kind of fierce, in a way—he had those eyes.

Peter wrote plays for the Mime Troupe.

He wrote some good stuff, and he wrote a really good article for the Tulane Drama Review. That’s an important article in the literature of theater. Peter was the smartest theoretician, or…the BEST theoretician. Didn’t always hang together, and it wasn’t always linear. He was seeing things on a bigger scale than everyone else. He was more, in a sense, poetic, really.

Peter fucking Berg wrote some good theater, goddammit. “Death of Hippie”? That was an event worth the trip. I remember packing up grass clippings, in little baggies, to hand out. [chuckles] Bags of grass!

Grogan was an action figure with charm to burn. He was one of the most charming guys. When he was on, he was fabulous.

Billy Murcott was always in the shadow, never really stepped forward. He was very important—certainly to Emmett. Emmett had a very lively imagination. He and Murcott, I think… I’d love to know really how much of it spills out of Murcott into… How much symbiosis there was. I don’t really know myself. Murcott, he was okay, but he wasn’t around, he wasn’t there, and he was never in front, ever, that I can remember.

What are your memories of Arthur Lisch?

Arthur Lisch was a good guy. He was a sweet cat, and he was a revolutionary in the most…calm way.

Sweet William [Fritsch]?

[affectionately] What a schmuck. What a crazy fucking bastard.

Claude.

Claude was absolutely the sweetest cat with absolutely the worst choice of an old lady ever known. H’lene. She was truly wacky—more than a little wacky. She had a fierce wacky look.

Speed…?

Maybe. I wouldn’t be surprised. Because there was so much energy being poured out at that time. Claude worked at Ramparts. Janie Schindelheim—Jann Wenner’s wife—she worked there in the advertising department. We spent a lot of time hanging out around the Ramparts offices, at that time, just kind of hanging out. That’s where the idea for the Digger Papers, which would eventually be published as a special issue of The Realist [download PDF here], originated, or gestated. Anyways, finally Claude came over to the dark side [chuckles] and hooked up with Chester and talked Gestetner into allowing them to lease or buy on time a Gestetner machine—which immediately went missing. [chuckles] And that’s it, that’s how all the broadsides occurred.

You know about David defending himself for getting busted for being a public nuisance for distributing broadsides? He was distributing one that he had written on the corner of Haight and Ashbury. The police arrested him for not moving on. And he decided to defend himself. It made the Chron! That made him into a little bit of a local hero, for standing up.

“Hippie Defends Self” or something was the headline.

And he won! Fucker! [laughs] He got a little advice from Dick Hodges, who was his roommate the summer at Berkeley and who was a lawyer, became a judge, is retired now. He was my lawyer during the rock ‘n’ roll days. That was a stunning thing.

The Communication Company stuff was everywhere. Not everywhere, but it was out there on a regular basis. So speed would not be a surprise. They were turning on…

Did you know Chester much?

It wasn’t possible. I hung out with him but I didn’t really know him. He was very elusive.

He was gay, apparently.

He might’ve been. There wasn’t a lot of gay sympathy at that time. In this group, it was sort of macho. Although all these people would be totally up with it… I don’t remember much gay presence at the Invisible Circus [a notorious Diggers event staged in a church in the Tenderloin], if any.

The Invisible Circus was so chaotic and out-there. There wasn’t enough of a plan. It was anarchistic. It wasn’t sustainable, and it was…24 hours? It was meant to be a whole weekend. It burned down when somebody got caught fucking, got caught by a church elder screwing on the church stage, man! Dave Hodges’ girlfriend, the guy who did the poster for the Circus, India Supra, I don’t remember what her real first name is, she was a squeeze of David’s I think. Dave Hodges, he was just a slightly wacky artist who was around, and he did an iconic poster, I think. Very important poster. [thinking] I have something from that Church, from when we got kicked out. A candle dampener. [laughter]

So during this period, I was already in the rock n roll business. The music thing was happening. I got into the music scene, got pretty involved. I was probably gone from the Mime Troupe when I started to invest a lot of time in the Miller Band. Steve Miller Blues Band. We used to get airline tickets for “Mr. Band.” (laughter) I had known Miller and Boz. Well, by then Boz had exited to Sweden because of draft issues. Steve was playing in Chicago. I went to Chicago. We hooked up again through friends we had known and also… and then he came to Berkeley. I went over, I started seeing some of the shows he was playing in places like the New Orleans house, or in San Francisco at the Matrix.

We, the Miller Band, would go set up and play in the Panhandle every couple of weeks. Somebody pulled a drop out of a street light, so we had power in the middle of the Panhandle, at the foot of Ashbury, maybe one block south. We played a lot. The Dead would come out and play. And there was that whole scene. Then the clubs started paying, and there was the Fillmore, and Bill [Graham] got it—this connects back to the Mime Troupe thing—Bill got it, and he produced one more, maybe two more Appeals. Then he got a license to do a concert at the Fillmore. And Family Dog had already done some concerts. So Quicksilver, the Dead, the Airplane, Big Brother, the Miller Band… Country Joe, everybody, there was a group of bands playing. A thousand bands. That became a viable business. The Miller Band got pretty successful. Not as successful as the Airplane, who then went with Bill. And then Bill kind of backstabbed the Family Dog in order to get the Fillmore exclusively. So Chet and the Family Dog crowd got the other ballroom, the Avalon, which was a great ballroom. And it worked. The summer of ‘66-7 was magic…

Kent probably has good stories. Kent was more on the street. But I did do some acid capping with Kent at his place. You get a gram of acid, you buff it out, you make 4,000 250mg hits by mixing it with, I think it was, baby milk powder. Something, some industrial product. Not industrial but chemical product. Brooks Bucher and Kent… Poor Brooks, I think he went mad. He was a good character, he was a fun character. And they lived way the fuck out on like 25th Avenue… Anyways, people would sit, when they were doing that, sometimes they would wear masks, which unless you have the right kind of mask is totally ineffective, and gloves, they would all wear gloves. And at the end of four hours, you were stoned, man. And that was it. You took these little gel caps and [makes dicing motion]. I think it was Owsley’s acid, although I don’t remember Owsley ever coming there. A middleman. Might have been somebody like Goldfinger, somebody, I don’t know.

Emmett claimed that he was involved with Altamont, took some responsibility for it going the way it did. What do you remember about it?

The Rolling Stones were somewhere doing their summer tour. 1969. I had already moved to L.A at that time. They had a house—well, they had a coupla houses—and one of them was the same one that the Beatles used. So there was gonna be a meeting. Grogan’s in town, Fritsch is in town. There’s gonna be a meeting with Mick tomorrow at Blue Jay Way. So we all went up there. We had heard that they wanted to do a big free concert, like the Beatles had done in London…? Maybe it was in response to…

Woodstock?

Woodstock, yeah. They wanted to do a free concert. Grogan put together a little group, [Grateful Dead manager] Rock Scully was in on it, so the idea was that this concert could be done by the crowd of people that was here. I was strictly Zelig; I was “good friend.” Mick came in, he had his guy James, publicist, this and that. And the pitch was, at that point it was going to be at Golden Gate Park. Speedway Meadow. That was great. And Fritsch said, Yeah and the Angels can provide security. Or actually Grogan brought it up and Fritsch, they must have talked about it, cuz he nodded. And that really appealed to the Stones, having Angels doing security, for a free concert, that sent them into overdrive. They were fantasizing. It was like the perfect Christmas cake event for them. If it had happened in that way, it would have been quite a crowning achievement.

Anyhow, so at some point, the Stones, who never do anything for free, I guess in their camp it was decided they would do a documentary of the free concert, and they were gonna produce it themselves, and then market it. So that was the thing. They were gonna do this concert video which could be turned into money and they would keep control of it. Well, then they couldn’t get Speedway Meadow. Melvin Belli couldn’t get Speedway Meadow. It was the stupidest thing the City of San Francisco ever did. I don’t remember the actual dialogue, but: no way, no how. He appealed… Melvin Belli, the toast of the citypolitik elite, couldn’t get it to work.

So now they had to find another venue. The next idea for a venue was Sears Point in Napa. They had existing facilities, they were familiar with crowds and so forth, although they wouldn’t be familiar with this size crowd… The reason why it didn’t go to Sears Point, and why there wasn’t really enough time to find another place, or to negotiate another place, was Sears Point was owned by Transamerica. United Artists was also owned by Transamerica. And UA was demanding as one of the clauses that they get the distribution rights to the documentary! And the Stones, out of stupidity, once again, wouldn’t make a deal with them. They could have, I know. I know I could have made a deal they could have both lived with, but they had got so headstrong someplace, that whoever was managing… [thinks] That’d be a good question for Mick. I don’t know why that went that way.

So Altamont, the whole fiasco of Altamont really boils down to one, San Francisco rejecting the use of Speedway Meadow, or the Polo field, or maybe they were the same thing; two, Sears Point, rejecting for United Artists, losing Sears Point, about 10-12 days before the concert. Hurry up, find a place, and what came of that was the Oakland Angels. Altamont was in their territory, because it was in Alameda County.

The San Francisco Angels had agreed to do security, but now the event was not in their hood. It was now in the Oakland Angels’ hood.

Right. The San Francisco Angels were in on the deal—all they wanted was to deal dope, get fucking high, hassle some people, fight amongst themselves, typically. That still would’ve been a mess but there wouldn’t have been this kind of mess.

There was a big difference in behavior/outlook between the clubs inside the Angels.

One of them had a sense of community, at that point, and one of them was just stone fucking criminals.

And if it hadn’t been a gloomy day, it wouldn’t’ve been so medieval. It was like what it must have looked like during the Crusades. Grey, smoky, almost foggy, dewy day, all day, never burned off. There were trash cans with fire in them, and people sitting on blankets, blankets over multiple people’s shoulders kind of thing. They smashed Marty Balin in the mouth. Just open anger. Truly, Rock has that story.

That day I was hanging with my little clutch of pals. Pretty relaxed. We found a comfortable place that was far enough away. Emmett was up on one of the sound and light towers. And I think he was up on the stage. He might’ve got punched out…

[musing] Emmett had it. When he started doing drugs in a serious way, he lost it. One of the last times I saw him, he pulled a gun on me once for getting in his face. He didn’t pull a gun on me, he had a gun, and I said, What the fuck is wrong with you, that you’re carrying a gun, that you have a gun? Who’s chasing you? What’s going on here? I said, You know, this is a direct result of using junk and having to scam all the time. Put the gun away. I said, Man you need to stop and get clear! And he, he didn’t put it up to here, but he put the gun and he said, You’re running a dangerous line. And I said, Emmett. We’ve been friends for too long and too deep. This is not where you should be, and this is not where I should be. And it was across the driveway from where I was living. It was at Lynn Brown and Vince Cresiman’s apartment, which was across the driveway from my apartment. And Emmett and Paula McCoy, who was his girlfriend towards the end, were staying there and Emmett had actually robbed a convenience store—I mean truly stupid shit! I didn’t see that happen but I believe that happened, and we had this confrontation and I just basically said I don’t think there’s any more we can say to one another. I’m certainly not gonna hang out while you’re holding a gun. And he never backed off of that, nor did he apologize…

But, I have another story. A few years before that. One time Grogan and Natural Suzanne and I went in my ’63 Corvette to Reno to gamble, in the winter. But we took LSD on the way, going up Highway 50. And when we got to the summit, basically near the Truckee area, the snow was falling in giant flakes—or at least they seemed giant—the road was passable. And the three of are squeezed into my corvette, Suzanne sitting in the center hump, and we started to just bloom. LSD coming on very strong! We decided to pull off and enjoy the snow for a few minutes. And we ended up playing in the snow at somebody’s summer home on the grounds, we didn’t get into anything, and making snow angels and we had the most marvelous time. And Grogan was TOTALLY FREE. Natural Suzanne was very relaxed and in a way…a supportive female, a little in awe of her circumstance, I thought at the time. But she was great, she was really great. Grogan, it was like he had completely emptied himself of his inhibition. Not that he got stupid! We were playing like children for a coupla hours. When we got back in the car, and I don’t even know if we ever got to Reno, we may have turned around and come back down, but meanwhile the road is pulsating! [laughs] Unbelievable! Emmett, my darlin’…

Emmett was a Roman Candle. I’m more like a long-burning ember.

Thank you for this, especially for those of us who were in far away lands at the time 🙂

peace be with you

LikeLike

Genuinely revealing and beautifully recounted.

LikeLike